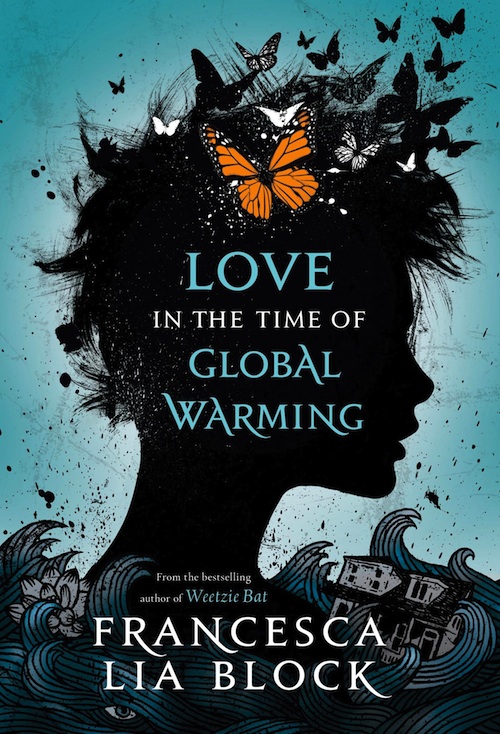

Check out Love in the Time of Global Warming by Francesca Lia Block, available August 27th from Henry Holt & Co.

Seventeen-year-old Penelope (Pen) has lost everything—her home, her parents, and her ten-year-old brother. Like a female Odysseus in search of home, she navigates a dark world full of strange creatures, gathers companions and loses them, finds love and loses it, and faces her mortal enemy.

The building has gold columns and a massive doorway, a mural depicting Giants, with bodies sticking out of their mouths like limp cigarettes. Someone besides me has studied their Goya. Bank of the Apocalypse reads a handwritten sign. It balances atop a pile of ruin-rubble and clean-sucked human bones. I can make out doors and windows, crumbled fireplaces, tiles, metal pipes, shingles, signs that read Foreclosure. The homes of so many skeletons. People who used to fight over the last blueberry muffin at the breakfast table, get down on their knees to scrub bathroom floors, and kiss one another good night, thinking they were at least relatively safe. Now they are just dust in the debris.

I climb through the rubble toward the door. It takes a long time, time enough for a Giant to see me from the blood-red stained-glass eye window and reach out to crush me in his hand the size of a tractor.

My mother never foresaw this danger. She was scared we would get sick from drinking tap water, eating genetically modified fruits and vegetables, even breathing the air. We had to put on sunscreen every day because of that hole in the ozone that kept her up at night. She gave us vitamins and bought us only chemical-free shampoo, even though it never made my hair as soft and clean as Moira’s. I used to hate how afraid my mom was and how afraid she had made me. Now I understand but I can no longer be like her. I have to fight.

The ceilings are so high I can’t see the top of them, and the only light is from the red glass eye. All around me are vaults that look like crypts. The whole place is a mausoleum.

“Here she is,” a voice says.

Not a Giant but Kronen emerges from the shadows, wearing a carefully constructed suit made of patches of dried, bumpy material. I force myself to stand my ground. The sword in my hand looks like a needle, even to me, though Kronen is only a few inches taller than I am.

“You’ve come back?” he says, smiling. It further distorts the uneven planes of his face. “I knew you would come back.”

“I want my friends,” I say. “You have my eye. You took my mother. I want to know what happened to her, and to my friends. And my brother.”

“Friends are important. Brothers are important. Sons, sons are important.”

“I know,” I say. “I’m sorry for what I did. But you had your revenge. An eye for an eye.”

“What will you give me if I don’t help you find them? A stick in the eye?” he muses.

I won’t let my hand go to the empty socket hiding under the patch. I won’t think of how that eye is gone, how it is as if every work of art, every beloved’s face it ever reflected, has vanished with it. If I saw madness in Kronen before, now it has exploded like a boil. That nasty suit—it looks like it’s made of dried skin.

“If you don’t tell me, if you don’t return them to me safely, I will kill you,” I say.

Kronen pets the strip of hair on his chin in a way that feels too intimate, almost sexual. His eyes roll up in contemplation. “I don’t know where your friends are,” he says cheerily. “Your dear mother died of natural causes, poor thing. Your brother got away from me.” Then his voice changes, deepens, his eyes stab at my face. “And you could not kill me if you tried. Have you forgotten who I am? What I have made? What I have destroyed?”

His laughter turns into shaking and the shaking comes from the steps of the Giant entering the room.

Now my sword really is a needle. And the color of fear dripping through my veins? Like our old friend, Homer, said, fear is green.

1

The Earth Shaker

The room was shaking and I thought I knew what it was because I had been born and raised in a city built on fault lines. Everyone was always dreading something like this. But we never imagined it would be of such force and magnitude.

I called to Venice, the most beautiful, smartest, sweetest (and he would want me to add most athletic) boy in the world, “I’m coming! Are you okay?”

I imagined his body lying under boards and glass, pinned down, but when I got to him he was just huddled in the bed in the room papered with maps of the world, wearing the baseball cap he insisted on sleeping in (in spite of the stiff bill), trembling so hard I could barely gather him up in my arms. My dad came in and took him from me—my brother’s legs in too short pajama pants dangling down, his face buried in my dad’s neck as Venice cried for his fallen cap—and I got our dog, Argos, and we all ran downstairs. My mom was there, crying, and she grabbed me and I could feel her heart like a frantic butterfly through her white cotton nightgown. We ran out into the yard. The sky looked black and dead without the streetlight or the blue Christmas lights that decked our house. I could hear the ocean crashing, too close, too close. The world sliding away from us.

The tall acacia tree in the yard creaked and moaned, and then my ears rang with the silence before danger. My dad pulled us back as we watched the tree crash to the ground in a shudder of leaves and branches. My tree, the one I had strung with gold fairy lights, the one that shaded parties made for teddy bears and dolls, the tree in whose pink-blossomed branches Dad had built a wooden platform house with a rope ladder. That was where I went to read art history books and mythology, and to escape the world that now I only wanted to save.

I was holding Argos and he wriggled free and jumped down and ran away from me, toward our big pink house overgrown with morning glory vines and electric wires strung with glass bulbs. I screamed for him and my mom tried to hold me back but I was already running. I was inside.

The floor was paved with broken glass from the Christmas ornaments and family photos that had fallen. (A tall man with wild, sandy-colored hair and tanned, capable hands, a curvy, olive-skinned woman with gray eyes, an unremarkable teenage girl, an astonishingly handsome boy and a dog that was a mix of so many odd breeds it made you laugh to look at him.) My feet were bare. I reached for a pair of my mother’s suede and shearling boots by the door, yanked them on, and stepped over the glass, calling for my dog. He was yelping and growling at an invisible phantom; his paws were bleeding. I picked him up and blood streaked down my legs.

I turned to open the door but a wall of water surged toward me behind the glass pane and I put up my hands as if to hold it back, as if to part the wave.

And then I fell.

That’s all I remember of the last day of the life I once knew.

2

The Pink Hand of Dawn

When i wake each morning—Venice’s baseball cap beside me and a photo of my family under my pillow—and feel the pink hand of dawn stroking my face, sometimes I forget that my mother and father and Venice and Argos are gone, that my best friends Moira and Noey are gone. I forget that I am alone here in this house, with the sea roiling squid-ink purple-black, dark like a witch’s brew, just outside my window, where once there existed the rest of my city, now lost as far as I can see. Even dawn is a rare thing, for usually the sky is too thick with smoke for me to see the sun rise.

When I did go outside, after the water levels went down, the smoke-black air, and the piles of rubble that had once been buildings, were the first things I noticed. Then I saw the giant frightful clown in the blue ballerina tutu; he used to preside over the city of Venice and now bobbed in the water among a banquet of Styrofoam cups and plastic containers. He was missing one white-gloved hand but still had his red top hat and bulbous nose, his black beard. The clown had made me drop my ice cream and run screaming to my mother when I was a child; now he looked even more monstrous. I saw crushed cars stacked on top of one another and the street in front of my house split in two, exposing the innards of the earth. Nothing grew and not a soul roamed. The trees had fallen and the ground was barren of any life, the world as far as I could see, deserted.

The debris of splintered buildings floated in swamps that were once the neighborhood where my friends lived. Moira’s family’s green and white Craftsman bungalow vanished; Noey’s mother’s 1960s apartment washed away. Had my friends run screaming, barefoot in their pajamas, from their houses into the street? If I listened, could I have heard their voices beneath the crash of the surf? Had they been killed in their sleep? Were they conscious when it happened, were they in pain?

I think of Moira’s ginger hair. Was it loose or braided? She sometimes braided it when she slept. I can see Noey’s watchful artist’s eyes, so round and brown in her round, dimpled face. Was she wearing one of her vintage punk T-shirts and men’s striped silk pajama pants? I can pretend my friends are somewhere out there alive but sometimes hope only makes everything worse.

It’s been fifty-three days since the Earth Shaker—I’ve ticked them off with red marks on the wall by my bed as if this small ritual will restore some meaning to my life. It’s early February but that doesn’t signify much anymore. No bills to pay, no homework due, no holidays. If things were different I might have been collaging Valentines for Moira and Noey and buying dense chocolate hearts wrapped in crinkle-shiny red paper for Venice.

I’ve cleaned the house as best I can, sweeping up the glass, nailing down loose boards. I tried to avoid bathing for as long as possible but finally, when the crust on my skin hurt, I gave in and now I use a minimal amount of the precious bottled spring water with which my anxious (overly, I once thought) father stocked the basement for a sponge bath every week and a half. I eat as little as possible from my father’s stockpile of canned foods to make them last. No one has come for me this whole time, which makes me think that this disaster reaches farther than I can see. But who knows what would happen if a stranger came. Perhaps I’m better off this way.

In the morning I try to make this half-dream state last, imagining Argos licking my face the way he was not allowed to do, because it might make me break out, but I let him anyway. Then I flip him over so he is on top of me, his body stretched out, belly exposed, big paws flopping, his tongue still trying to reach me from the side of his mouth, even in this position. Above us, the da Vinci, Vermeer, Picasso, Van Gogh, Matisse, and O’Keeffe prints (torn from broken-backed art books found at garage sales) papered the low attic ceiling like a heaven of great masterworks. (They are still here, though damp and peeling away from the wood.)

I imagine my mother calling me from downstairs that breakfast is ready and I am going to be late for school, calling for Venice to stop playing video games and come down and eat. I cannot smell, but I try to imagine, the scent of homemade bread and eggs cooked in butter, the mix of sweet jasmine and tangy eucalyptus leaves baking in the sun. The sharp smell of turpentine in which my mother’s paintbrushes soak, the sight of her latest canvas on the easel—a two-story pink house in a storm on the edge of a cliff with a sweet-faced boy peering out the window. The sound of the sprinklers zizzing on outside, the throaty coo of doves in the trees.

I tell myself that when I get up and go downstairs my mother will say, “Brush your hair, Penelope. You can’t go to school like that.” This time I will not make a comment, but kiss her cheek and go back up and do it, thinking of how Moira spends hours each morning straightening her hair sleek and how Noey’s black pixie cut is too short to need a fuss. I will eat the oatmeal without complaining, I will be on time for school and not consider Venice High a highly developed experiment in adolescent torture.

I try to imagine that my father will be drinking black coffee and reading a book at the kitchen table. He is sleepy-eyed behind his horn-rim glasses, smelling of the garden he tends each morning, about to go to work (this is before he lost his job and the depression and paranoia set in), looking like someone who could take care of anything, not let anything bad ever happen to his family. And that my brother will be there, with his hair standing up on the back of his head, his sturdy, tan little legs, and his dirty sneakers that get holes in them after just a few weeks. I will not complain that he has finished all the orange juice, is chirping songs like a bird, asking too many questions to which he already knows the answers—Penelope, do you know how magnets work? Can you name a great African-American orator from the 1800s? What team scored the most home runs of all time?—or is wearing my basketball jersey. I will notice that his eyes are thoughtful gray like the sea at dawn, our mother’s eyes.

But now all of this is as magical and far-fetched and strange as the myths my father once told me for bedtime stories. Shipwrecks and battles and witches and monsters and giants and gods are no more impossible than this.

Because, when I force myself to rise from my bed unbidden by anyone, and go downstairs, unbrushed, unanointed (my mother would not mind; it is safer this way in case any marauder should find me), the simple breakfast scene will not exist. The house will be broken and empty, the sea encroaching on the yard, the neighborhood flooded, the school—if I dared venture there—crumbled to scraps of barbed wire, brick, and stucco, the city named after angels now in hellish devastation as far as I can see. A basement full of canned goods and bottled water that my father provided, with more foresight than most, sustains me for another day that I do not wish to survive, except to await my family’s return.

Fifty-three marks on the wall. If the world still existed, wouldn’t someone have come by now?

Like the dead orchid beside my bed, I am still alone.

Love in the Time of Global Warming © Francesca Lia Block